6 Elements of Police Spin: An Object Lesson in Copspeak

- Submitted by: Love Knowledge

- Category: Media

The linguistic gymnastics needed to report on police violence without calling up images of police violence is a thing of semantic wonder. Officers don’t shoot, they are merely “involved” in shootings; victims are not victims, but “suspects” “fleeing”; human beings become premortem cadavers as bullets “enter the torso” rather than the chest of a person; guns and bullets act on their own as they “discharge” or “enter the right femur,” rather than being fired by autonomous individuals with agency and purpose. Headlines become 14-word, jargon-heavy tangles where a simple five-word description would suffice.

Last week, the case of Ohio Deputy Richard Scarborough shooting and killing 16-year-old Joseph Haynes inside a courthouse checked off nearly all the pro-police propaganda tropes:

1. The Classic ‘Officer-Involved Shooting’

The most overused of copspeak cliches, “officer-involved shooting”—or in this case, “deputy-involved”–appeared in headlines reporting Haynes’ killing:

- “Teen Defendant Dead After Deputy-Involved Shooting Inside Franklin County Courtroom” (WBNS-10TV, 1/17/18)

- “Mother of Teen Shot and Killed During Deputy-Involved Shooting Demanding Answers” (ABC6, 1/18/18)

The addition of “involved” to these headlines adds nothing, obscures much and takes longer to read. The first ought to say, “Deputy Shoots Teen to Death in Franklin County Courtroom” (9 vs. 11 words); the second could have been written, “Mother of Teen Shot, Killed by Deputy Demanding Answers” (9 vs. 12 words). These headlines would be more efficient with the added bonus of explaining what actually occurred.

The purpose of saying “officer-involved”—as others have noted before—is to obscure responsibility. A bizarre construction, it does not appear in other contexts. (Can one imagine the headline, “Man Dead After Gang Member–Involved Shooting”?) It’s a thought-terminating cliche, a ready-made assemblage of words that does the thinking for the reader in service of a political end—in this case, protecting the police from bad PR.

2. Smearing the Victim

The 16-year-old Haynes was referred to as a “defendant” (the complete summation of his position in life), and his juvenile record was mysteriously leaked to the press in a matter of hours after his death. Here, a local news station, 10TV, spends 30 seconds of a two-minute broadcast rattling off the victim’s priors, despite their having zero to do with what occurred in the courtroom that day:

As FAIR has noted before (3/4/15, 3/22/17), any dirt on victims of police violence seems to be made readily available to the media (most often by the organization responsible for their death, the police), while, as in this case, the identity of the officer “involved” is initially kept private—an arrangement that protects state institutions while pathologizes their victims as malevolents who had it coming. (Only the tail end of coverage later revealed Scarborough’s name, at which point he was praised for his “good work record”—AP, 1/23/18.)

3. A Vague ‘Altercation’

Frequently when a police officer shoots and kills someone, a department spokesperson claims there was an “altercation” that preceded the killing. “Altercation” is a term broad enough to span two parties yelling at each other to deadly combat, which is exactly the point. In this case, the police claimed Haynes’ killing followed an “altercation” of unspecified severity and symmetry:

- “The victim’s hearing on a menacing with a gun charge was just wrapping up when family members and a deputy got into an altercation, [Chief Deputy Rick] Minerd said.” (CNN, 1/17/18)

- “A 16-year-old boy was fatally shot by a deputy in an Ohio courtroom after an altercation involving the victim’s family, according to authorities.” (New York Post, 1/17/18)

But the use of “altercation” to launder police guilt is common. In the case of Walter Scott, for example, his summary execution at the hands of South Carolina police officer Michael T. Slager was originally described as an “altercation” by local press parroting police language (FAIR.org, 4/8/15), until a video of the shooting surfaced days later showing Scott being shot in the back while running away. Claims that Scott had “gained control of the taser to use it against the officer” were shown to be demonstrably false, something pulled of thin air by police PR and echoed by compliant local reporters. Slager was later found guilty of second-degree murder and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

It was unclear even in later coverage what the “altercation” in the Haynes case entailed, but certainly when the news was fresh, when the bulk of reporting appeared, this single word did a lot of work to justify the killing of an unarmed 16-year-old to the public—with little or no skepticism by media.

4. The Organization That Did the Killing as Sole Source

Virtually all the initial reports of Haynes’ killing quoted only the police and had no word from his family. This CNN report (1/17/18) is nonstop quotes by the police, who drive the narrative entirely:

It likely would have been easier if CNN had just had the police department write up the story for them.

5. Obscuring—or Omitting—Who Killed Whom

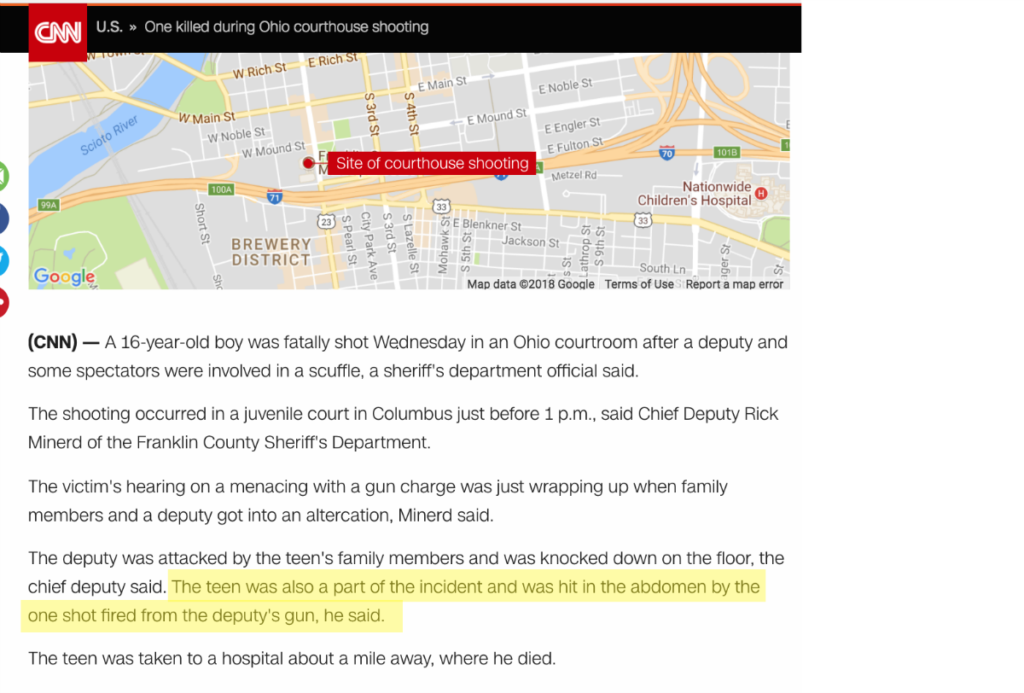

The same CNN piece goes four paragraphs before saying who actually died. (Nor does the headline, “One Killed During Ohio Courthouse Shooting,” provide any specifics.)

Even then, it’s unclear who did the killing. The teen, “part of an incident,” was “hit in the abdomen by one shot from the deputy’s gun,” apparently an autonomous entity.

A report by ABC13 (1/18/18) took it one step further, writing an entire article that never says, in any way, that a police officer shot and killed someone:

The closest we get to actually assigning responsibility is the sentence “during the dispute, officials say the deputy got knocked to the ground and one shot was fired.” Fired by whom? At whom? A news report logs 120 words about an incident and none of them, strung together, actually explain the purpose of the report’s existence.

Someone died, a deputy was in the area. How those two are related is never made clear. The most responsible party appears to be an inanimate gun.

Which brings us to our final element of copspeak:

6. Rogue Weapons

CNN reported:

The teen was also a part of the incident and was hit in the abdomen by the one shot fired from the deputy’s gun, he said.

Notice the teenager isn’t shot by the deputy, but by his gun. The passive, sterile language reads like a police report, because that’s exactly what they’re rewriting. Crime reporters for the most part mimic the dehumanizing language of the police—up to the use of “hit in the abdomen” over “shot in the stomach.” Facing a story about a child whose life has just been instantly erased, beat reporters do their best impression of a jaded forensic medical examiner on Law and Order.

Taken to its absurd extreme, this guilt-diffusing rhetoric takes us to coverage like this NBC Bay Area headline (1/17/18) about police killing a man with a taser:

Warren Ragudo, 34, wasn’t killed by the police, he simply “died after” they tased him (or, more bureaucratically, “deployed a taser on the individual”). Let’s not leap to the conclusion that 25,000 volts jammed into someone’s chest might be related to their death seconds later. The brute causality is linguistically massaged with passive language.

A human being becomes an “individual.” “During a struggle” washes away all questions of who started what, what the details were and whether such a “struggle” justified the use of deadly force are assumed to be non-issues.

Unless you’re reading, say, a meditation on Leibniz’s Monadology, complex and jargon-heavy writing is a red flag for deception. Why do these reporters and editors take simple, straightforward events such as one person shooting and killing another and turn it into rhetorical highwire act?

In stories of police killings, the police should first of all be the subject of scrutiny. Instead, more often than not, they serve as sole sources and often virtual co-reporters. That they should be afforded this special status because they represent state power—the very institution that a free press is supposedly intended to serve as a check on—makes this unearned and deeply conflicted position of privilege that much more perverse.

Read more https://fair.org/home/6-elements-of-police-spin-an-object-lesson-in-copspeak/

Related items

-

The New COINTELPRO? Meet the Activist the FBI Labeled a “Black Identity Extremist” & Jailed 5 Months

The New COINTELPRO? Meet the Activist the FBI Labeled a “Black Identity Extremist” & Jailed 5 Months

-

Poor People’s Movement Continues Wave of Nonviolent Civil Disobedience

Poor People’s Movement Continues Wave of Nonviolent Civil Disobedience

-

Stop Using Discriminatory AI, Human Rights Groups Say

Stop Using Discriminatory AI, Human Rights Groups Say

-

How to Wrestle Your Data From Data Brokers, Silicon Valley — and Cambridge Analytica

How to Wrestle Your Data From Data Brokers, Silicon Valley — and Cambridge Analytica

-

Voices from the Mass Shooting Generation: Youth from Around Country Descend on D.C. to Demand Change

Voices from the Mass Shooting Generation: Youth from Around Country Descend on D.C. to Demand Change